The attraction of the Honda 305 Dream is best understood as being in the right place at the right time in the history of motorcycling in the United States. At the end of World War II, there were fewer than 200,000 motorcycles registered in the United States. The majority of the available motorcycles were medium to large sized Harley-Davidsons, Indians, Triumphs, and a variety of other British makes. The majority of those purchasing these motorcycles were either returning servicemen from World War II or technically and physically competent men in the 30 to 45-year-old age range. These motorcycles utilized engineering that hadn't changed much from the late 1920s to mid-1930s. They required a strong right leg to kick them through – usually multiple kicks after a complex series of actions involving choking the carburetor, priming the engine, retarding the ignition, and saying various prayers to the gods that ruled over whether the motorcycle would start or not. The wiring systems were little more than cobbled spaghetti bundles wrapped in tape and burlap and then shellacked for some water protection. Reliability was poor at best.

Even though the engineering was old and simple by today's standards, driving and controlling these machines was complex. The throttle control, usually on the right side handlebar, was controlled by the right palm of the hand. The front brake, also mounted to the right handlebar, was controlled by the fingers of the right hand. The ignition advance was controlled on the left side handlebar. In order to shift gears, the clutch was depressed by the left foot while removing your hand from the left handlebar grip and changing the gear shifter mounted to the left side of the tank. Try doing this in a higher-speed turn, in the rain, with trucks in front of and behind you – and not lose control. The rear brake was controlled by the right foot and required careful modulation to not lose rear tire traction. In summary, there were six functions controlled by two hands and 2 feet, each hand controlling two functions each. The brain had to coordinate all six functions while at the same time actually riding the bike to where you want to go. Riding a motorcycle was and is a complex and often counter intuitive enterprise. For example at any but the slowest speeds, you actually steer right to go left – this is called counter steering. The sheer amount of skill required of the motorcyclist in this era was daunting.

Once started and pointed in the right direction these large displacement, mostly twin cylinder motorcycles, shook andvibrated so much that they could make your kidneys bleed and your dental fillings fall out. It was only a question of time that most of the nuts and bolts that held everything together would unscrew themselves and parts would start to fall off. Suspension systems usually involved a few springs on the front wheel with a few inches of travel, and nothing on the rear except the air in the tire and a spring under the seat. When you hit a bump, everything would start to oscillate up and down and side to side for a period of time proportional to your speed and the size of the bump. During this time, it was the skill of the rider that saved the day from total catastrophe. When the ride was over, the rider would take note of how much oil had sprayed onto their pant legs (from the engine, transmission, oil tank, and grease flying off the rear chain drive) as well as how fast a pool of oil was forming underneath the engine. Suffice to say that to be a motorcycle rider in the postwar era – until the early 1960s – required a level of physical strength, mental skills, and an emotional steadiness and courage that only a few percentage points of the population possessed.

Despite these requirements to ride a motorcycle, the number of registered motorcycles in the United States tripled in the 17 year period between 1945 in 1962 to approximately 600,000 motorcycles. But then something amazing happened. In a three-year period between 1962 and 1965 there was another nearly tripling of registered motorcycles to approximately 1.5 million!

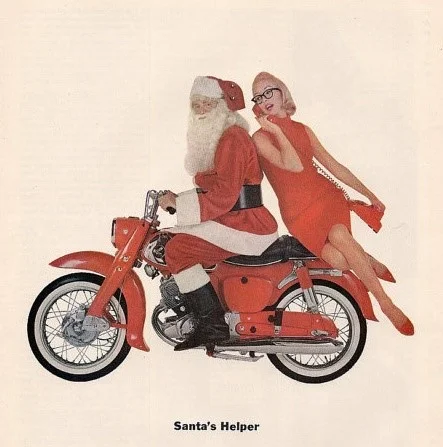

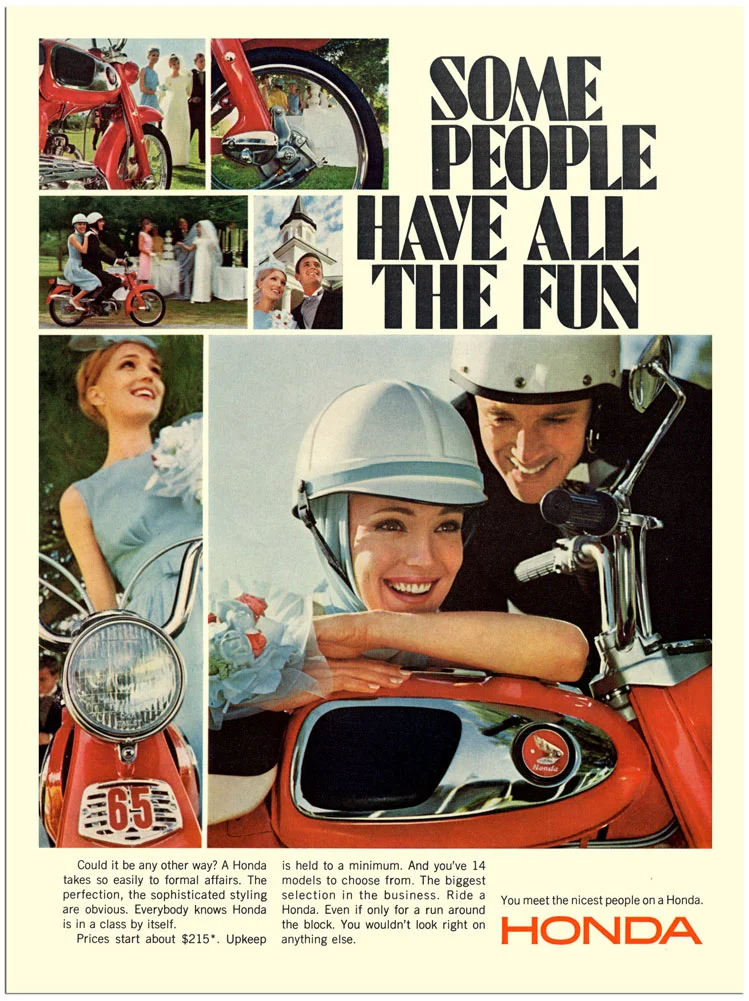

What happened in 1962 was an advertising campaign by Honda motorcycles which featured the following statement: "You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda!". Advertisements in all types of media featured clean cut younger people in the 18 to 40-year-old demographic riding a new sort of motorcycle. Instead of the sort of motorcycles described above, often being ridden by a socially marginalized person like a character out of the famous 1953 movie "The Wild Ones", these Hondas were a new kind of machine. Instead of being large and intimidating, they were smaller to medium sized and looked inviting. Their paint schemes, whitewall tires, sparkling chrome and integrated designs seem to say – "I want to be your friend – let's go for a ride". The people shown riding these motorcycles in these ads look like the boy and girl next door – always smiling and having a great time. These were indeed the nicest people – and they were riding the nicest motorcycles. They looked like anyone in that age demographic – perhaps somewhat idealized – might look. These ads made you want to be like them and made you feel that if they could and did ride these bikes that you could and would ride these bikes. 10 years after this most famous of advertising campaigns, the number of registered motorcycles in the United States had doubled again to approximately 3,000,000. A significant percentage of that growth was due to massive sales of Honda and other Japanese marques. Honda had single-handedly convinced the younger side of the population of the United States that motorcycles were appropriate for anyone and not just the few superhumans that could handle the old technology motorcycles of yesteryear.

The ads drew people into the rapidly expanding dealer network around the country. Instead of entering an often dark and less than clean Harley or Triumph dealer, Honda motorcycles modeled their dealerships after new car dealerships. They had standardized dealer signage and featured bright and clean showrooms with big posters on the walls from the "You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda" advertising campaign. In a Harley or Triumph dealership, the salesman was also the mechanic. When you came through the door and the little bell rang notifying him of your being in the show room, you would hear him grumbling as he got out from underneath the bike he was working on. He would walk in from the back service area to greet you with little more than a grunt, wearing mechanic overalls, as he wiped off the 60 weight oil from his permanently stained hands. The Honda dealerships on the other hand featured neatly groomed, smiling and gracious salespeople who were wearing polo shirts and khakis. These were nice people selling nice motorcycles in a nice dealership. There was no fear or intimidation to overcome.

Then you looked at the motorcycles. They were so clean and bright and welcoming – it was almost as though they were smiling at you. The salesman would show you the starting drill. Unlike the 5 minute procedure described previously, starting a Honda motorcycle was like starting a car in that era. Turn the key, pull on the choke, hit the electric start button. Instead of the old technology where starting the engine induced coughing, choking, and belching, followed by smoking and thunderous vibration. The Honda started instantly and immediately settled into a sewing machine like contented purring. Once the old technology motorcycle was started it was saying "okay, you got me started – so if you got what it takes maybe I won't kill you today". The Honda was saying "see how easy it is to start me – it's equally easy to ride me down the road. I'll help you in every way to ensure your safety. You will arrive clean and refreshed and safe at your destination. Once there, you will meet other nice people on nice motorcycles like me”.

Further inspection of the details of these Honda motorcycles revealed an integrated design where everything looked as though it had been thoroughly thought through. The old technology motorcycles, particularly Harley Davidson, looked like a collection of parts – each one added and bolted on where it was most convenient for the manufacturer but not necessarily the rider. There was no more hand shifting systems fixed to the side of the tank. Rather, shifting was done by the left foot and the clutch was on the left handlebar. What a concept – you don't need to take a hand off the handlebar in order to shift gears! The engine cases were split horizontally making oil leaks a thing of the past. The rear drive chain was completely encased so that no oil would fly off onto your clean khakis. There were both front and rear suspensions so that going over bumps was not damaging to your internal organs. The wiring harnesses featured high-quality insulation, modern snap connectors, and other components making them worry free. What was not to love?

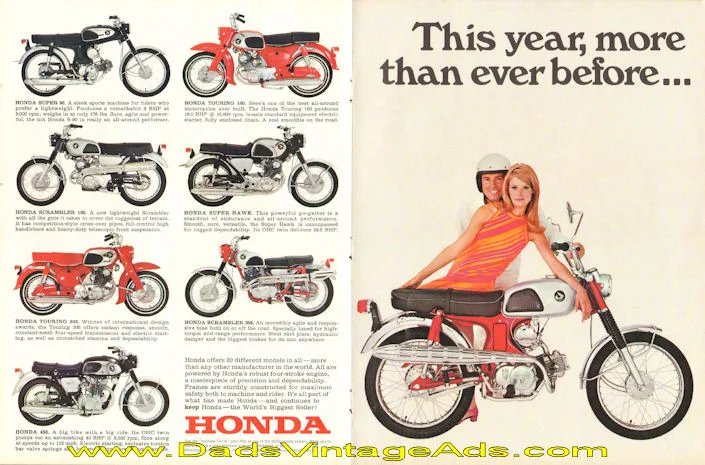

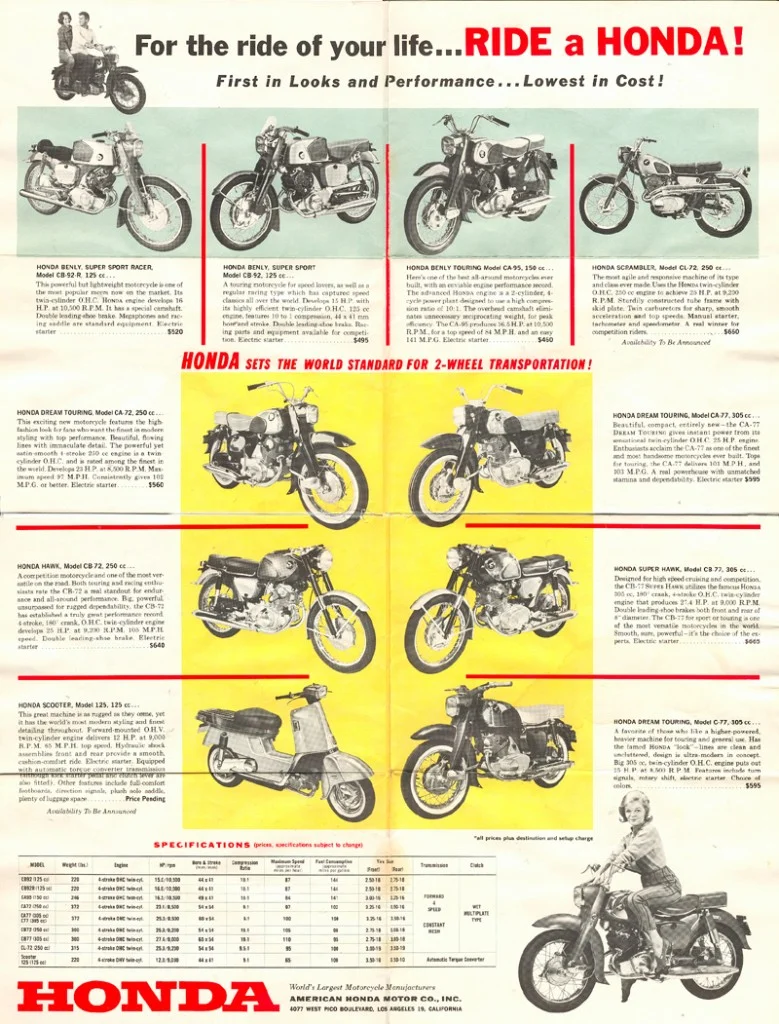

The other critical elements in Hondas (as well as other Japanese makers) success was offering a line of motorcycles that started with minibikes that could be easily written by a six-year-old all the way up to their biggest motorcycles – all 305 cubic centimeters of them – that could serve an adult doing some "touring". Most importantly, MSRP ranged from approximately $350 to approximately $600 from the bottom of the range to the top, so there was little financially to inhibit purchase. Therefore, any potential customer lured into the dealership by the ad campaign would find the perfect size machine at the right price. How nice is that?

So with this history in mind, imagine a group of young boys, like me and my friends, between 10 and 12 years of age. We all learn to ride tricycles and bicycles as we venture farther and farther from the warmth and safety of our homes out into the infinite goodness of the universe. My friends Bobby and Don and Geoff and Sandy were all different in what bicycles we wanted and how we rode them. There were Schwinn Stingray's and Collegiates and Raleigh English racers. There were Murray cruisers. Some of us wanted to go faster and farther (like me), and some of us just wanted to go a little ways to the local convenience store for some pretzels and Dad’s root beer.

Everybody progresses differently. Everybody learns in different ways and at different rates. It's no different when it comes to our relationships with vehicles. Like most kids, I started out on a red tricycle that you could sit on and it wouldn't fall over if you did nothing at all-requiring no movement or balance. Then my dad put my hands on the handlebars and my feet on the pedals and began to push me forward. The pedals turned under my feet and eventually my brain got the message that if I continued to push the pedals with my legs I could propel myself all over the place. Step two was on to the balancing game on a two wheeled bicycle, first with training wheels and then amazingly without them. But the real addiction to two wheeled power was a neighbor’s minibike powered by a Briggs & Stratton 3.5 horsepower lawnmower engine – WOW! Just turn the right-hand throttle and go! Interestingly, of all my bicycle buddies, only Bobby enjoyed the motorized version of two wheeled excitement. But his involvement never match my level of enthusiasm and passion.

So after that first minibike ride at age 12, I was able to locate and trade some chore money, comic books, baseball bats and some baseball cards for my first minibike. Unfortunately, there was a large space in the middle of the frame that used to have an engine – now missing. I eventually took an engine from a discarded from an old lawnmower and got the thing running. I became quite a hellion on that thing. Now most kids would've stopped after their first minibike ride. They would have sensed the inherent danger in going that fast with no steel cage around you for protection. But I realized I could control this device and loved the feeling of speed and freedom and the wind in my face. Like I said before, we all learn in different ways and at different rates and I did not want to stop learning about going fast on two wheels. The mini bike proved to be just an appetizer that only wetted my appetite for a “real motorcycle”.

In order to decide which would be the perfect motorcycle for myself I did what I have always done. I read as much as I could find on the topic, analyze it thoroughly, decide on the top two or three options, and then finally let my heart decide among those final options. Every week on Saturday morning, my parents took me to the South Euclid library in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio. We would spend a couple of hours browsing and picking out a couple of books to read during the week. But now I found myself bolting immediately for the magazine room which contained every imaginable magazine on every imaginable topic! That included Cycle and Cycle World and Motorcyclist magazines. I read them all cover to cover poring over words that described the engineering of the motorcycles. Words like telescopic fork tube versus Springer versus leading link front suspension, vertical versus boxer twin cylinder engine, chain drive versus shaft drive, overhead cam versus pushrods, unit versus pre-unit engine construction, concentric versus monobloc carburetor and 5.00 by 16 versus 4.00 by 18 tires. I absorbed the commentary regarding the performance of the machines. There were words like "this motorcycle turns into corners intuitively with minimal effort". There were words like "the brakes worked fine for two or three stops but then faded rapidly". There were words like "vibration was minimal to the handlebars and foot pegs until 4500 RPMs when it became intrusive". Finally, there was the performance data which included all of the vehicle specifications such as wheelbase, dry weight, seat height, tire sizes and tank capacities. My eyes always went to the 0 to 60 time, the quarter-mile time, and top speed. Blessed with a good memory, I soon knew every performance and specification parameter from most every motorcycle available in America. If I ever read my history lessons in school with as much interest I would've gotten an “A” on every test.

So now my task was to actually learn to ride, not just read about, these machines. By age 13 I got to know where every motorcycle within a several mile radius was located and which of my friends and older brothers had access to them. So I was able to procure rides, experience, and increasing confidence with Honda Mini Trails, CT-70s, and ultimately my first "real motorcycle" ride – a Honda S 90. I learned to coordinate throttle and clutch and hand and foot brakes. My motorcycle trajectory was on its way straight up to the sky. Beside my burgeoning interest in girls, there was nothing that occupied my interest more intensely or that I found more thrilling than gliding over an asphalt ribbon. I flew through backyards and alleyways, up and over median strips, and along the country roads to the east of our home in Pepper Pike, Ohio. These were the same roads that seem to take all day, pedaling furiously on our bicycles, just to go the seven or 8 miles to our favorite turnaround point – Squires Castle in North Chagrin Reservation on Chagrin River Road. Now we could be there in 10 or 15 minutes by just twisting the throttle and following the snakelike road leaning into each turn like a surfer on a wave crest. On a warm summer afternoon it was euphoria.

During that summer of 1968, my backyard neighbor Drew told me he had seen a bright red motorcycle pulling into the driveway three doors down from his house. So for the next several days in the afternoons and evenings Drew and I would hang out playing catch in his front yard and reading from his extensive comic book collection. One evening, Drew pointed out a gentleman pulling his car into the driveway of the house three doors away. Fifteen minutes later, the garage door opened and the man pushed a bright red Honda 305 Dream out into the early evening sunshine. Recognizing it from the advertisements and magazine tests I knew that this was the "gentleman's touring" version in the Honda motorcycle lineup. The true sporting version that I had dreamt about was the CB77 superhawk with a true telescopic tube front fork suspension and twin carburetors. Maybe it was the way the evening sunlight reflected off the chrome panels on the side of the gas tank, or the way the front and rear fenders curve around their respective tires and flared out in the rear, or the way the square headlamps seem to match the squared steel pressings of the front fork and the upper portion of the rear shock absorbers – somehow it just looked perfect. Even the dual passenger seat was red, a place for me in the front and a girlfriend behind. It also looked like a big motorcycle to me at the time. It seemed like a real man's motorcycle – but somehow inviting and not intimidating – yet full of potential for performance and definitely exciting. At that moment I completely forgot about the true precursor to all future superbikes – the CB 77 Superhawk and switch my dreams to the Honda 305 Dream.

I ran over and introduced myself to the old man – he was probably all of 28 years old. I started asking questions about the bike which he had recently purchased from Sill’s Honda motorcycle sales not too far away. He said he had looked at the Honda Superhawk but liked the style of the Dream. He said he didn't need a racing bike, just something to take him and his wife out for an afternoon ride. He revealed a few technical subtleties that I had to go research over the next week. Whereas the Superhawk had a 180° crankshaft, meaning that the Pistons went up and down in alternating fashion, the Dream had a 360° crankshaft where both Pistons went up and down together. He said this was more like a Triumph Bonneville and resulted in more low-end torque and gave it a more throaty sound. He pointed out that most motorcycle engines were completely surrounded by their frame. The Dream however, had an engine bolted to the front of the pressed steel frame, and acted as a stressed member of the frame. Canted slightly forward, the engine seemed to portend its ability to propel the machine forward through space. Having studied the engines on Harley-Davidson's, Indians, and the British machinery, the fins that cooled the cylinders and the engine castings all seem to be more perfectly casted and put together. The "fit and finish" seemed more fine and perfected to my sensibilities. I was in love for the first time. In love with a hunk of metal, but in love nonetheless.

All I could think about was how to get a ride on his bike. That weekend, I came up with a plan. I borrowed my friend David's Honda S 90 and rode over to Drew's house and read more comic books for several hours until the gentleman came home. I hopped on the S 90 and rode over to the Dream’s owner. We talked more motorcycles and I started to hint to him that it would sure be great to try out the "big" motorcycle. Why he did it I'll never know. Maybe because of my unbearable enthusiasm and because I left the other bike for collateral- at one point he said "why don’t you take it out for a spin-just get back in an hour because I plan to take the wife out for a ride".

My heart was beating out of my chest as I pulled on my Bell RT helmet on this warm Saturday afternoon. I was wearing my "safety gear" which included a white T-shirt, Levi's, and a pair of white Jack Purcell tennis shoes! To this day I can hear the engine start up the moment I touched the starter button. I pulled back on the left side handlebar clutch lever and pushed down with my left foot on the gear shifter and I could feel first gear engage confidently. I twisted the right-hand throttle grip and the engine with a deep and mellow sound increased in RPMs. I blipped it two or three times feeling the potential power between my legs. The one thing I did not want do in front of him was stall the engine on takeoff. There was no tachometer on this bike, so I turned the throttle up somewhat more than I needed to and then slowly let the clutch out and went out into the street for the first time on a real man's motorcycle! I waved to him as I slowly rode down the street.

As soon as I got out from his hearing range, several streets away, I opened the throttle up. Accelerating down Gates Mills Boulevard which had a large median strip and very little traffic accelerated hard through the gears. What a sensation! I looked down at the speedometer and it read 55 miles an hour – than 65 miles an hour – then suddenly I realized that there was a stop sign about 100 yards down the road. I squeezed on the front right brake lever and pushed my foot into the right rear brake pedal. With small drum brakes not much was happening! Now my heart was really pounding! But somehow the Honda Dream didn't let me down and came to a stop just before that stop sign. I made a vow then and there to never let myself get out-of-control or overly excited again on one of these big machines.

It was then that I realized that I was occupying the front half of the dual passenger seat but the rear was wide open. Five minutes later I pulled up to Lynn's house. I turned the bike off and set it up on the center stand. I angled the bike pointing out the driveway to make it even more inviting and ready to go for a ride. I hung my Bell helmet off the left side handlebar like I had seen the cool bikers do so often. I rang the doorbell which was answered by Lynn's mother. I very politely asked if Lynn was home and if I could talk to her. No one could be more polite and courteous than me when I wanted to be. After Lynn came out and I had honestly answered all her questions regarding where I got the bike and did I know how to ride such a big bike – and could we go to the Dairy Queen for some ice cream – she finally consented to a ride. Her mother came out and told us to be careful and seemed to be reassured when I told her it was a Honda. As we drove over to the Dairy Queen the dual sensations of Lynn holding on tightly from behind and the power of the motorcycle so easily carrying both of us up to speed was intoxicating. It was then that I realized I only had $.35 in my pocket so we had to share a single scoop of vanilla with two pink plastic spoons. After this first motorcycle ate, I dutifully dropped Lynn off telling her I would soon be in possession of a Honda Dream of my own so we could ride off into the sunset together. I got back and gave the Honda Dream back to its owner and rode home on the Honda S 90. The S 90 now felt like a bicycle by comparison. Going down the same road I had hit 65 MPH on previously – I was now only able to achieve 40 MPH. So began the addiction to speed.

The next weekend, Drew's older brother who had his driver's license, drove us out to Sills Honda motorcycle sales. The big red Honda sign with white letters out front was visible many blocks before we arrived. They had about 10 motorcycles lined up on the sidewalk in front like sirens in a Greek play beckoning you inside. Once inside I couldn't get over the sheer size of the showroom. There had to be at least 50 motorcycles ranging from 50 CCs to 305 CCs. Because of my experience of the prior weekend I immediately gravitated to a series of three brand-new Honda 305 Dreams sitting in a row. Like freshly cleaned newborn babies – they were simply perfect! One was white, one was black, but my favorite was the red Dream with the red seat. On the side cover the dealer had put a small chromed sticker that proclaimed it was being sold by Sill’s Motor Sales. The fresh black rubber of the tires had all the little nubs proclaiming their virginity. The chrome on the side of the tank and on the wheels gleaned with perfection. The curves of the front fender integrated perfectly into the curves of the gas tank which then flowed up and over the rear wheel in one smooth line.

My dreams of all day rides with Lynn behind me were suddenly interrupted by someone walking toward me. A nice salesman, well groomed, in khakis and a polo shirt came up and asked me if I was interested in buying a motorcycle. I said yes. He asked if I had a motorcycle license. I said I would be getting it "soon". He then started to steer me back down the line away from the big motorcycles down toward the Mini Trails. I dutifully looked at them as he told me about their specifications and performance. Having memorized all of that previously, I did not argue when he got a few of the details wrong. He then excused himself and gave me time back with my 305 Dream. There was a cardboard placard hanging off the handlebar that proclaimed its MSRP at $595.00. Having about $.35 in my pocket I knew there would be no sale that day.

So fast forward 30 years. I'm married to the love of my life – Diana, not Lynn. We have two beautiful children and are living in California – a place where you can ride motorcycles every day! I decided that it is now time to realize THE DREAM. I had to go find the perfect 1968 Honda 305 Dream. There was no eBay or online searches yet, so every week I bought a local recycler magazine and perused the advertisements for classic bikes. Every month, I picked up the only national classified advertisements for motorcycles called Walneck’s. After locating and evaluating approximately 20 or 30 thrashed and beat up and misrepresented Dreams I finally saw an ad in the Walneck’s national magazine. It advertised a 1968 Honda 305 Dream that had only 2100 miles on it. It was said to be completely original and in “museum” condition. When I called the phone number, a man answered the phone saying –“Buzz Walneck” here! I was actually speaking with the owner of the periodical. He said he had found the Dream at the Mid-Ohio Race track’s vintage motorcycle meet. He indicated it was an incredible find. He had purchased it from the family of the original owner who had passed away a few years earlier. He said the motorcycle had lived its entire life in a extremely well insulated temperature controlled garage in Cleveland, Ohio. The original owner had purchased it in 1969 as a 1968 model. He drove it approximately 3 or 4 times a year between the spring and the fall before winterizing it and repeating the process the next year. He had documented the dates and mileage before and after each ride, gas fill up and servicing. Over the nearly 30 years of his ownership he averaged only 70 miles per year! His daughter said that he thoroughly detailed and waxed the bike almost every time he rode it. Buzz said it was the nicest 305 Dream he had ever seen and that it ran perfectly. He chuckled when he said “it still has the original tires with original “OHIO AIR”. A deal was struck immediately and the bike was on its way to California by truck the next week.

Upon its arrival I could feel my heart beating rapidly as though I was 13 years old once again. As the driver opened the rear of the truck I saw the familiar red curves offset by the angled sheet metal and rectangular headlamps. The chrome on the side of the tank and the wheels gleamed. As he pulled it down the ramp I saw a small sticker on the side panel of the bike. As I read it, my heart almost stopped – it said "Sills Motor Sales – Cleveland Ohio".

Later that evening in my garage, after cleaning and detailing the bike, I decided to check the air pressures in the tires. I unscrewed the cap and opened the Schrader air valve. The unmistakable aroma of old tire air filled my nostrils and seemed to penetrate into that part of my brain that held those precious memories of my Honda Dream DREAMS. I’m sure to this day that a few of the air molecules in those tires were in the air at Sill’s Motor Sales that day 30 years earlier-now magically reunited with me.